A fresh approach to rationing land for new development is needed to avoid another 50 years of housing failure

What does that mean for Real Estate?

Mortgage interest rates are correlated to the rates in the bond market so, as bond yields rise, banks will raise their mortgage rates. For commercial markets, the result is that capitalization rates will reduce as mortgage rates rise. With less net income, buyers will want to reduce their purchase price so they can still make a reasonable profit.

For Residential buyers, it means that they will either have to buy a less expensive house or be able to pay a higher mortgage. For many first-time buyers, it will put the dream of home ownership out of reach.

Murtaza Haider and Stephen Moranis, Special to Financial Post

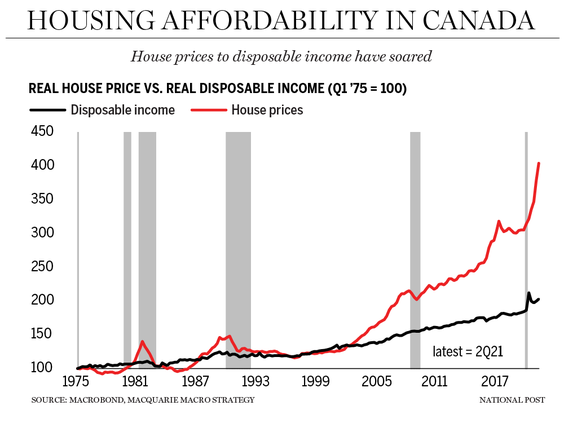

The general narrative around housing in Canada points to worsening housing affordability as of late. Implicit in the argument is the assumption that owning or renting a house was perhaps affordable in the past.

Many fear that rising housing prices have pushed the dream of homeownership out of reach for many young Canadians, but perhaps that’ not really a new development.

“If you don’t own a house by now, there’s a strong chance you never will. That’s the central, disturbing fact about the most widespread —and least understood —social revolution of our times.” Those words resonate today with most Canadians who are dismayed by rapidly escalating housing prices and rents. But here’s the catch: they were written 55 years ago in Maclean magazine’s May 1967 issue carried a detailed expose of the deteriorating state of housing affordability in this country.

“The idea of a separate house for every middle-class Canadian family is just about extinct,” the story continued. “Suddenly, no one can afford it anymore.”

Housing prices in the late sixties, of course, were a fraction of what they are today. For example, the average price of a house in Vancouver in 1966 was $15,200. In desirable parts of the city such as West Point Grey, the average price was $42,000.

Rents were also deemed unaffordable. Two-bedroom units in trendy Vancouver neighbourhoods rented for $250 or more. Back then, rental advertisements mainly appeared in newspapers. Prospective renters would queue up outside the Vancouver Sun office to grab the paper’ first edition to get a head start on apartment hunting.

Housing was even more expensive in the East. The average price in Toronto was expected to be more than $30,000 in 1967, a jump from $20,000 in just two years, Maclean’ reported. Thanks to the forthcoming Expo 67, which put Montreal and Canada on the world stage, housing prices and rents were escalating fast in that city, too. In the Maritimes, housing challenges were even more acute. The average price of a new home in Halifax touched $30,000 in the late sixties.

Those prices sound reasonable today, but they weren’t considered so at the time.

Canada’s housing crisis goes back even further. “The truth is that throughout the 20th century Canada has been in the midst of a continuous housing crisis,” Albert Rose, a professor at the University of Toronto, wrote in Canadian Housing Policies, his 1980 book chronicling the state of housing from the 1930s to the 1970s.

He observed that even from 1920 to 1945, Canada had not done enough to meet “the human and statistical criteria for decent and adequate housing accommodation.” Housing, in general, has been in a state of continuing crisis, but housing affordability has gone through various ups and downs, at least since the 1990s.

What differentiates housing markets since the 1990s is the gradual and sustained decline in interest rates that have kept average mortgage payments at less than 40 per cent of average income. Thus, even when housing prices climbed at an unprecedented rate, the accompanying decline in interest rates kept mortgage payments relative to income in check.

The reasons behind the country’s housing challenges have also remained similar for more than half a century.

Housing supply and the scarcity of developable land is a challenge today, but it was also a challenge back in the fifties when most Canadian cities had consumed the available serviced land for development.

Local governments are required to have a running inventory of serviced land to accommodate future growth. For example, municipalities in the Greater Toronto Area are required to maintain a minimum of three years’ worth of continuous supply of vacant registered and draft approval lots.

Yet a report from Ryerson University’ Centre for Urban Research and Land Development concluded that “an insufficient supply of serviced lots is the primary reason why the supply of new ground-related housing in the GTA has fallen short of demand.”

The housing crisis has persisted in Canada to a large extent because of supply-side failures. A fresh approach to rationing land for new development is needed to avoid another 50 years of housing failure.

You must be logged in to post a comment.